Enjoy the “Kill” on DVD now Available on Amazon.com

Out of work Kimsy and her irritated mother butt heads over Kimsy’s lack of effort in trying to find a job and help out with responsibilities around the house. After a particularly nasty argument, Kimsy storms out to walk off her frustration in the quiet surrounding woods. Instead of lowering her blood pressure, Kimsy’s blood runs scarred and runs down her head as she’s knocked out and picked up by a playful serial killer with an irreparable hate for women and takes gratification in degrading them by any means possible. Sadistically bred by unconditional motherly abuse, the killer treats each of his prized possessions like dogs to submit to his every beckon and call. Kimsy’s mother and sister, Camilla, grow concern for Kimsy who hasn’t returned home and set off to find her. When they realize she’s been abducted, they’re able to track her to a remote, vacant cabin used as a kill house and as they set foot inside the cabin to save Kimsy, a killer lies and waits to strike.

Lars-Erik Lie’s Norwegian torture porn, “The Thrill of a Kill,” resonates with the old and true proverb, what comes around, goes around. Filmed in and around Norway’s largest ski destination and resort, the Scandinavian mountain town of Trysil becomes the backwoods abattoir for the director to set his exploitation workshop for the bleak Norse horror. “The Thrill of a Kill” is the first feature length fictional film from the Norway-Born Lie who has digs into the indie underground and gory storytelling, self-funded by his own banner, Violence Productions, and is coproduced by Morten K. Vebjørnsen and Arve Herman Tangen, Morten Storjordet, and Linda Ramona Nattali Eliassen serve as executive producers.

Dichotomizing “The Thrill of a Kill” into two stories set during two different time periods, Lars-Erik Lie’s focal point is not the hapless victims caught in a deadly spider’s web of perversities. Instead, Lie’s story formulates the theory on how the sociopathic killer was ill-nurtured into a monster with an interweaving plot set in 1968 of a young boy (Carl Arild Heffermehl) neglected and abused, verbally and physically, by an alcoholic and sexually promiscuous about town mother (Sonja Bredesen) who would bring home another town drunk to bed. Missing his (deceased?) father and tired of being bullied by his own mother, the boy mental state snaps like a twig under immense emotional, family-oriented pressure and descends into a murderous madness. Years later and all grown up, the maniac mountain man abducts young women as a direct result of the hate toward his mother and her mistreatments. Arve Herman Tangen becomes the goateed face of the grown man gone haywire. Tangen develops his character with purposeful intent and with a nonaggressive tone to persuade his bound quarry to remain subdued. The role is nothing short of typical that we’ve seen in other films of its genus where a screwed-up child-turned-adult runs a deviancy amok sweatshop of imprisoned flesh and torture devices and Tangen really adds nothing meaningful to derangement. In her debut and only credited role, Kirsten Jakobsen, former Model Mayhem model from Oslo, succumbs to being the unlucky alternative girl, Kimsy, that runs into the big, overwhelming man while strolling through the forest. One would think Kimsy would have suffered brain damage after being struck and knocked unconscious not once, not twice, but three times by the killer who undresses her after each time with the third and final blow putting the final touches on his toying with the girl and bringing her back for a visit to his hen house of brutalized women. After the first blow or two, Jakobsen doesn’t show that much concern for Kimsy’s attentive wellness or concern as Kimsy continues to just wander as if nothing major has happened. Camilla Vestbø Losvik is a much more reliable and realistic rendition of the situation as Kimsy Sister, Camilla. As another alternative and attractive woman, Camilla shares a strong kinship with Kimsy despite their mother’s disciplinary differences toward them, to which eventually their mother (Toril Skansen) comes around as the patron saint of motherly worriment that’s likely a contrasting parallel to the killer’s unaffectionate mother. With an ugly-contented subgenre, “The Thrill of a Kill” has various compromising positions for its cast with rape and genital mutilation that there’s some shade of respect give to those who can mock play the unsettling moments we all are morbidly curious to see. The film rounds out with a lot of half-naked women strung up in bondage or chained to the wall with Linda Ramona Nattali Eliassen, Veronica Karlsmoen, Veronica Karlsmoen, Madicken Kulsrud, and Ann Kristin Lind with Raymond Bless, Niclas Falkman, and Jarl Kjetil Tøraasen as drunk, male suitors.

“The Thrill of a Kill” recreates the simulacrum of SOV horror as Lars-Erik Lie pulls out his handheld video to follow Kimsy’s journey through the jollies of a madman and the mother and sister’s rout out for their lost Kimsy. The beginning starts off with a zombie-laden dream sequences that places Kimsy in a field with a killer and his mutilated corpses that reanimate in a bit of foreshadowing of what’s in store for the spikey haired damsel. By dismissing her vividly horrifying dream of diminutive meaning, just like she does with everything else, Kimsy falls easily into the killer’s hands signifying one of the films’ themes to never take things for granted, especially those things that are important to you as exampled later on in the story. That’s about as much purpose I could pull from out of Lie’s film that floats like a feather on surface level waters. There is one other tangential offshoot Lie attempts to explored but never fleshes out fully is the unbeknownst to Kimsy and Camilla’s perverted hermit of a father who lives on the outskirts of town. Their mother thought he would have insight on Kimsy’s whereabouts but instead he tries to forcibly coerce Kimsy into his shack for involuntary lovemaking and then the exposition ensues after Camilla barely escapes his axe-chopping in (sexual?) frustration clutches. That exposition literally goes into a tunnel leading to nowhere and doesn’t alter the actions of Camilla or her mother to do anything different, expunging any kind of knowledge to utilize for a complete character arc and just comes to show Lie’s written bit parts don’t define the narrative of learned opportunities or gained instinct but rather are just additional sleazy show. The same sleazy show can be said about the rape scenes as they won’t ascertain the intended reaction of squeamish uncomfortableness. Now, while rape is no laughing matter or accustomed at any degree, there’s a level of numbness to these scenes that carry a severe flat affect to doesn’t display the anguish, the terror, or the hurt these women are going through as the killer decides upon himself to violate them. There’s literally no fight in these undrugged, still vigorous, young women who have just been snatched and made into his plaything and while some seasoned BDSM partisans may get aroused, the emotional receptor in me wants to empathize what their strife agony, but maybe that’s why the film is titled “The Thrill of a Kill,” to be an emblem of fun, cheap thrills.

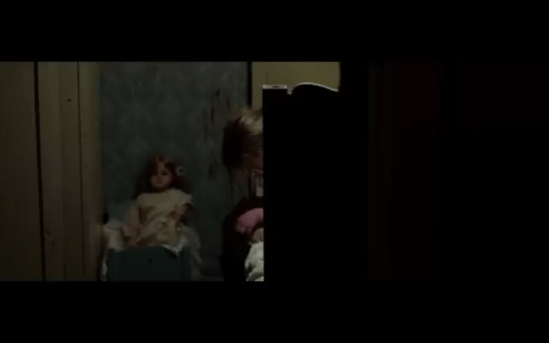

Coming in at number 70 on the spine, the Norway schlocker-shocker, “The Thrill of a Kill” lands appropriately onto the Wild Eye Releasing’s Raw & Extreme banner. The 2011 released film finds a vessel for its North American debut over a decade later after its initial release and presented in a 1.33:1 aspect ratio, with vertical letterboxing on 16×9 televisions, despite the back cover listing a widescreen format and being released in 4:3 is a bit surprising as other countries display in anamorphic widescreen and the lens used in the film is definitely anamorphic as you can tell with flank falloff that distorts the image and makes the picture appear rounded. Color grading is slightly washed and lives in a low contrast. Again, I have to wonder how aesthetically different the transfer is on the outer region product. Soft, SOV-equivalent details don’t necessarily kill the image quality, but you can obviously notice some pixelation in the frame inside the shack and in wider shots of the landscape amongst the low pixelated bitrate. The Norwegian Golby Digital Stereo 2.0 comes out clean, clear, and about as full-bodied as can be with a two-channel system. Some of the Foley is overemphasized production which comes off sillier than the deserving impact of a thrown punch or a meat hook going through the lower mandible. English subtitles are burned/forced into the picture but are synched well without errors though the grasp maybe lost a little in translation. Bonus content is only a trailer selection warehousing select Raw & Extreme titles, such as “Hotel Inferno,” “Acid Bath,” “Morbid,” “Bread and Circus,” “Absolute Zombies,” “Whore,” and “Sadistic Eroticism.” Continuing to achieve maximum controversial covers, Wild Eye Releasing doesn’t hold back for “The Thrill of a Kill” DVD with a crude, yet fitting DEVON illustrated cover art that is a platterful of unclasped splatter while in the inside is a still frame of one of the more tongue biting scenes. No cuts with this unrated release and the film clocks in at 85 minutes with a region free playback. A grating gore gorger with mother issues, “A Thrill for a Kill” redundantly recalls our attention back to the subservience of what makes horror horrifying and while what terrifies us is pushed aside, the free-for-all fiend-at-play treats the death-obsessed to a buffet of blood and defilement.