Order the #34 and #35 of a “Chinese Courtesan” from Imprint Asia’s Boxset!

Taken against her will while living off the streets, Ai Nu’s kidnappers take her and other snatched girls to the Four Seasons Brothel where the once homeless young girl is greeted by the elegant Chun-yi, the brothel head mistress whose cold and ruthless, but Chun-yi, despite letting Ai Nu be whip beaten and raped by her prestigious paying clients, falls for Ai Nu’s beauty. The two women form a close, sexual relationship while Chun-yi continues to sell Ai Nu’s body to the wealthiest bidder. All the while, Ai Nu plans her revenge, slow and steady to get back to those who exploited her. That’s the harrowing and melodramatic exploitation premise, streaked with reality-defying Kung-Fu, from a Shaw Brothers production and its reenvisioned remake that diverges itself from the original story with additional elements that influence what type of revenge Ai Nu is plotting and provides alternate emotional context to the principal characters.

“The Intimate Confessions of a Chinese Courtesan” and “Lust for Love of a Chinese Courtesan” are the 1972 original and the 1984 remake violent martial arts and brothel underbelly love, rape-revenge narratives brought together by Via Vision’s Imprint Asia sublabel. These films pushed the moral fiber envelope with prostitution decadence, scandalous lesbian themes, and sexual violence displayed on Hong Kong’s cinematic screen. “Haunted Tales’” Yuen Chor, credited as Chu Yuan, helmed the Kang-Chin Chiu (“Finger of Doom”) script of “The Intimate Confessions of a Chinese Courtesan” with Chor returning over a decade later to sit back in the director’s seal for the remake, “Lust for Love of a Chinese Courtesan” in which he wrote the script that keeps most of the core similarities that mildly varies yet significantly differs the emotive motivations that affect the finale and character outcomes. Both films are a production of Shaw Brothers with Runme Shaw producing “Intimate Confessions” and Mona Fong, wife of Runme’s brother Run Run Shaw, produced the “Lust for Love” sequel of the “Chinese Courtesan.”

Power, under an affluential and admired ruling thumb backed by the wielding of Kung-fu arrogance, is what Chun-yi of “Intimate Confessions” embodied and, eventually, is what blinded her to her undoing. In her debut role, Betty Pei Ti creates an unforgettable impression that cements Chun-yi as a fierce and fixated force being a corruptor of young women and a criminal kingpin with her deadly mitts in just about every provincial authority and lawmaking body. The “Police Woman” and “Succubare” actress seizes one-half control of the story with her beauty, acting command, and dynamic and complicated relationship with on screen actress Lily Ho as Ai Nu, a homeless young woman with equally fierce fight in her but not backed by any kind of authority or station. Ho, a veteran actress with stardom success as the titular character from Chih-Hung Kuei and Akinori Matsuo’s female fatale picture “The Lady Professional” the year prior, brings a vulnerable ferocity to Ai Nu. Like a scared cat back into a corner, Lily Ho claws the character through a no-win-scenario of survival in a tough role that involves multiple men thrusting themselves onto her but like a switch, Ho’s able to turn off Ai Nu from being an erratic rebel to save her life to actually saving her life by calmly weaponizing love. Kuan-Chen Hu portrays the Ai Nu character a little bit different in the 1982 version. Not as feisty and more brittle, Hu’s uno card reversal on the brothel mistress turns into a ménage à trois of greed in it’s underlaying of revenge. Chun-yi, too, has varying traits to the “Intimate Confessions” counterpart as On-On Yu (“Black Magic with Buddha”) gives the brothel mistress, who goes by Lady Chun, a softer harshness when it comes to delicate and delegating dastardly business and personal affairs. Lady Chun also doesn’t have a martial arts bone in her body unlike Betty Pei Ti’s fighters-of-death Chun-yi who is a more of a typical well-rounded, boss-level antagonist, but what Lady Chun does come with more is contextual backstory, a woman who rose from power but sees much of herself in Ai Nu and makes promises of reciprocal care with fellow orphan and childhood friend, and skillful hired sword assassin, Hsiao Yeh (Kuo-Chu Chang, “Killer Rose”). On-On Yu’s version can be cruel but be cruel while exacting a tender heart to her fixation on Ai Nu, adding a deeper and different complexion to what we’ve seen Chor produce before more than decade before. The cast of each film round out with kidnapping scoundrels, crooked officials, and one lone decent constable within a supporting cast that includes Yueh Hua, Lin Tung, Wen-Chung Ku, Fan Mei-Sheng, Chung-Shan Wan, Shen Chan, Alex Man, Miao Ching, and Kuo Hua Chang.

Watching the two films back-to-back can throw one for a loop as the remake is not a carbon copy of the original, but there is a lingering familiarity that can’t be shook as it hooks itself to “Intimate Confessions’” key plot and forcibly exclaims its remake existence. Like many things that have a sense of duality, there are also stark and contrasting differences between them. If personally favoring sadist measures, rougher sexual confiscating, and a confident villainous vixen, the original “Intimate Confessions” will be more to your like. If personally favoring a slow-and-steady wins the race melodrama, brewed and stewed in romance and storytelling, with more wuxia fighting and swordplay, the “Lust for Love” checks the boxes. Compositionally, Chor’s vivid backlighting through a hazer fog with different spectrum colors is evident in both films but “Intimate Confessions” has profound designed objects and background combinations that work with the choreography that tells the mood of the story: the windy and hazy night of Ai Nu and the good natured constables first meet that tells of a foreboding fate, the the bright and joyous revelry of exciting patrons of on the verge of copulating with exploited, kidnapped young women, or the darker streaked toned of betrayal and death in the finale showdown between principal players. “Lust for Love” also has a tone about it that’s more in tune with the melodrama with expensive looking sets accompanied by a delicate palette of gold, white, and softer reds and yellows. Plenty of third act loving making from the love triangle showcase told through a sequence of surrealism and teeing up fantasy desires heightened by the glisten outdoor tub water sloshing side-to-side in their passion, on the dewy moss the half-naked roll in, and in the gold rimmed adorned bedrooms where lesbianic lovers flirt. Chor first ventures the rough rape-revenge thriller only to chuck the indelicacies of the original film and replace with swirling succulence of sex and self-indulgence, a contrasting brilliance formed and reshaped only a dozen years apart.

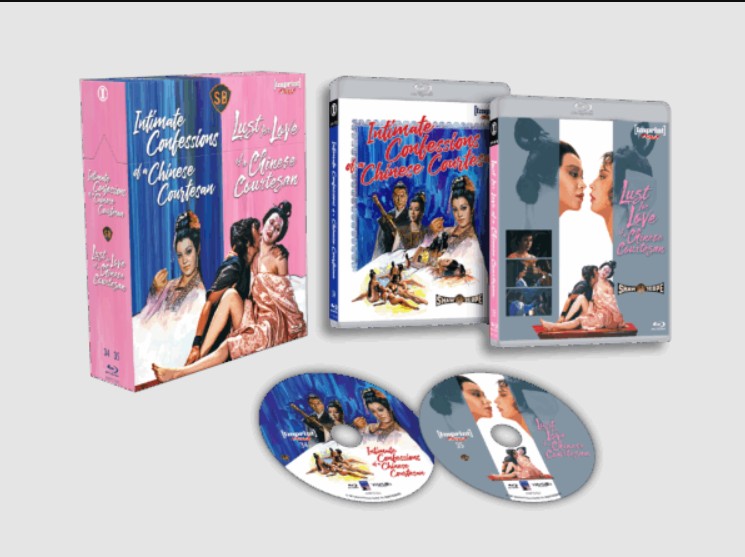

Imprint Asia knows all about courtesans, or at least about the Yuen Chor courtesans, in “Intimate Confessions of a Chinese Courtesan” and “Lust for Love of a Chinese Courtesan” with a new 2-disc Blu-ray boxset from Australia. The 1080p high-definition transfers are pulled from the original 35mm negatives and are AVC encoded onto a BD50s and presented in their original aspect rations of 2.40:1 (“Intimate Confessions”) and 2.35:1 (“Lust for Love”), compressed by spherical anamorphic, widescreen lens with the noticeable curvature in the image. Both presentations offer an ideal image experience with neither damage showing signs of damage or age, palpable textiles of the silk-spun and cotton blend garbs that sheen as expected and absorb a gratifying amount of reflected light within its respective fabric. Grain appears light yet organic with skin tones and textures with an organic display, unlike in the Shaw-Shock Volume 2 set where skin coloring appeared orange in quite a few scenes. The spherical lends offers depth despite its slightly warped edging as if looking in a corner convex mirror. The audio formats include a Mandarin LPCM 2.0 Mono mix with burned-in English subtitles. There’s also a Cantonese language option of the same spec but the English subtitles are optional. Subtitles synchronization is on point with the ADR track that’s retains a clear and discernable dialogue albeit the gurgling quality of recording interference present through. The over exaggerated transcript on top of its equal over exaggerated performances, especially with the googly-eyed and giddy older village officials looking to score handsomely with the courtesans, is present in every inch of a less-than-seductive prostitution rendezvous. Soundtracks boast a melodramatic and action pack score with an extremely westernized design only fiddling slightly with traditional Chinese melodies and with Fu-Liang Chou adding some harsh guitar during the spicier segments of Ai Nu’s lesbian grooming. Chin-Young Shing and Chen-Hou Su provide a more classic and harmonically sound for “Lust for Love” to exact more passion and heart and less depravity. Special features or “Intimate Confessions” include a new audio commentary by author Stefan Hammond and Asian film expert Arne Venema, a new informational and highlight discussion from film historian Paul Fonoroff, an archived featurette directed by Frederic Ambroisine Intimate Confessions of 3 Shaw Girls takes the female perspective and review from journalistic critics and actresses including one actress for the films, an archived interview featurette with critic and scholar Dr. Sze Man Hung, critic Kwan King-Chung, and filmmaker Clarence Fok, and rounds out with the original theatrical trailer and DVD trailer. “Lust for Love,” in comparison, is more barebones in bonus content with an audio commentary by film historian Samm Deighan and the DVD trailer. The physical presentation is similar to Shaw-Shock Volume 2 but just a slightly be slimmer with a jagged tooth topped, rigid slip box with a line split down the middle of the front cover depicting illustrations of characters for each film in either a contrasting blue or pink background. The backside has a compilation of melded together pictures from both films. Inside, two clear case Amaray, complete with their own original one sheet as cover arts with a reverse side having pulled a scene from their respective film, sit snug inside the slip box. The boxset has a total run of 3 hours and 6 minutes, is not rated, and is region free.

Last Rites: Yuen Chor’s dichotomy of the two films is an odd and rare accomplishment of the filmmaker’s re-envisioning of his own work but “Intimate Confessions of a Chinese Courtesan” and “Lust for Love of a Chinese Courtesan” have idiosyncratic merit despite the same underlining premise and now it’s showcased in a brilliant boxset from Imprint Asia for you to decide Ai Nu’s revenge and motivations in the fray of brothel captivity.