“School in the Crosshairs” on a Cult Epics Blu-ray! Purcahse here at Amazon.

Yuka Mitamura is the smartest, most well-rounded student at her high school that’s embattled by a constant debate on whether physical edition and clubs are a necessary requisite for academic success, jeopardizing physical activities such has her best friend Koji’s Kendo club. When Mitmura’s latent psychokinetic powers emerge, she struggles to cope with the change that’s out of her control and the new acquaintances with similar powers that show up in her life, such as with new female student Michiru Takamizawa whose sudden enrollment sees a quick rise in the ranks of school politics and sparks an insidious need for a totalitarian and fascist reign to control dissident and unapproved behavior within the school. As an oppressive crack down on the total student body sparks a civil war amongst the students, Michiru and her mentoring demon Kyogoku aim to enslave the human race and it’s up to Mitamura, unknowingly Earth’s champion, to fight against the forces of evil.

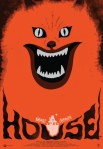

Adapted from the 1973 science fiction and fantasy novel “Psychic School Wars” by Taku Mayumura, “School in the Crosshairs” is every ounce those Japan famous hyper-intensity and colorfully assertive commercials with visual sparkle and great enthusiasm for their hawked products. You know them well when they go internet viral. The 1981 Japanese adaptation is helmed by Nobuhiko Ôbayashi, director of “Hausu” and “His Motorbike, Her island,” from no script but rather from Mayumura’s novel as script. Keeping faithful to nearly the entire novel and adding Ôbayashi’s variegated touch, “School in the Crosshairs” is a flamboyant Earth invasion in its divisive influence of the study body, especially between the studious academics and physical clubs. Also known as “The Aimed School” and “School Wars” elsewhere in the world, as well as titled “ねらわれた学園,” ”School in the Crosshairs” is produced by “Island of the Evil Spirits’” Haruki Kadokawa, who also produced our last Japanese reviewed title, the traumatically powerful and wonderfully performed “The Beast to Die,” under his company Kadokawa Haruki Jimusho.

“School in the Crosshairs” circles around principal character in film and in book Yuka Mitamura as she juggles her newfound powers. Between feeling like a stranger in her body as well as the weird visitations of her powers and of the otherworldly figure with a cap and green skin and having to not only rebel against an authoritarian rule overtaking her high school but also to save all of the world from that said otherworldly and powerful figure, Mitamura’s plate is undoubtedly full for a teenage girl. Hiroko Yakushimaru (“Sailor Suit and Machine Gun”) comes to the role as a teenage girl herself at the age of 16-17 years old by the time of principal photography and seizes the high school melodramatics with ease as the carefree smartest kid in school. Yet, finding Yakushimaru a formidable character stemmed by her performance is not so easily rendered in an indifference projection toward her newfound abilities; Yakushimaru is unable to really compel audiences with body language or even in her dialogue on why the teen has to soul search cope when she discovers she’s different. We get more out of Ryôichi Takayanagi (“His Motorbike, Her Island”) as the quasi love interest and Kendo club leader Koji as his kendo tournament matches and failings in academics that affect his beer story-owning family dynamics are heavily emphasized and given more weight against a floundering leading lady character with superpowers and uses those powers to put Koji in good standing amongst the Kendo culture with win-after-win. Not until the world starts to unravel at the hands of fascist student leader and fellow telekinetic Michiru Takamizawa (Masami Hasegawa, “The Tragedy in the Devil-Mask Village”) and her despot leader, the manipulative demon Kyogoku (Tôru Minegishi, “Main Line to Terror”) in a technicolor brilliance of a cosmic showdown held within the interdimensional layers but even then the last gasp of defeat has lackluster strength after a mountainous buildup of dictatorship control and potential student civial war. The cast fills out with Keiko Mitamura, Noriko Sengoku, Yûsuke Okada, Kôichi Miura, Hiromitsu Suzuki, Macoto Tezuka, and Kôichi Yamamoto.

Pushing a few of the acting and character flaws aside and off the table, “School in the Crosshairs” is essentially manga embodied by live-action film. There’s stellar mass group choreography near the beginning when the clubs merge for a rush invite to encourage recruitment, there is an extravagantly caped character in green makeup and a white afro wig, and there’s the painted-on-cell colorization I’ve mentioned a few times already that really ups the fantastical sci-fi features of Mayumura’s novel with a director like Nobuhiko Ôbayashi unafraid to get deep with saturation and long in experimentation. Themes on fear of individualism, forced conformity, friendship, and the rise up out from that powerlessness feeling for what’s right showcase through metaphorical fascism, akin to the likes of the evil Nazi Germany party with a fear mongering nationalist’s convincing motivational speeches and confidence commands that seduce the ears of the waning high school minority, the academic kids, seeking alternative solace and a way to regain control as they are not as popular in contrast to those in clubs. The Nazi tropes don’t end there as rounding up nonconformists, Nazi-like uniforms, and even a modified heil make their way into the overall story and that’s the darkest part in “School in the Crosshairs” light and airy jeopardizing of innocence and individuality.

Catching a glimpse of Nobuhiko Ôbayashi’s pre-“Hausu” filmmaking brilliancy is now as easy as catching “School in the Crosshairs” on a North American Blu-ray release from Cult Epics. The dazzling high-definition and an equally impressive, supplemented release is AVC encoded onto a BD50 with a 2K transfer and restoration of the original 35mm print and presented in a widescreen 1.85:1 aspect ratio. The “School in the Crosshairs” restoration visuals need to be seen to be believed in a newly graded touch up that offers a glassy darker side within the fascism themes and a richer color palette to make the hued pinwheel spectrum a living, breathing character between good versus evil. The grain comes through naturally on nearly all scenes with some of the shadowy moments favoring less delineation through the consistent optical texture. The composited effects are boldly vibrant inside a creative streak that’s idiosyncratic only to Ôbayashi and are implemented into the live scenes with precision that doesn’t make it awfully clumsy or clunky. Cult Epics made sure to cover any and all viewer’s at-home audio setup with three Japanese language options: an uncompressed LPCM 2.0 Stereo, a Dolby Digital 5.1 Surround Sound, and a DTS-HD MA 5.1 Surround Sound. Each carry their own weight and attributes with the LPCM 2.0 and DTS-HD 5.1 similar in fidelity, but the DTS offers an expansive girth that fills in the left and right channels of interdimensional ambience with laser strikes and gameshow tonal keys. Dialogue is constructed through ADR that carries a level and balanced layer field and holding its own against the fantasy ambient that sometimes rises to meet the dialogue decibel; however, dialogue is clean and clear without any issues in clairaudience. Newly improved English subtitles are optionally availably. The set is quite complete, and likely comprehensive, with the physical and encoded special features. Film critic Max Robinson offers a feature parallel commentary track, Phillip Jefferies provides a video essay on Nobuhiko Ôbayashi’s body of work in Sailor Suits and Sound, an Ôbayashi film poster gallery, and the theatrical trailer. Physically, the clear Blu-ray Amaray case keeps inside the reversible cover art with both sides featuring the Japanese poster arts and housing that package is the limited edition cardboard O-slip with a fantastic compositional design by Sam Smith. Inserted inside is the back cover unlisted, 22-page booklet full of black and white as well as color adverts, feature stills, characters bios, and other writings but all in Japanese, no English. The 90-mean feature comes no rated and is region free.

Last Rites: More so now than ever in the current political climate, freedom of expression endangerment is the critical theme for Ôbayashi’s “School in the Crosshairs,” a color melange of resistance against the forces of evil hard to differentiate looking like our friends, family, and the everyday student.