The Best Depiction of the Unpleasant Side of Brothels. “Broken Mirrors” on Blu-ray.

An Amsterdam brothel Happy House Club clings to the good girls that remain employed to pleasure the reprobate and insensitive johns that visit. Dora, a virtual working girl lifer, brings in new blood, Diane, a young mother desperate in need of financial support because of her drug addicted husband. Night after night, customers select through the ever-growing service list the club’s owner deems profitable while the women and the matron manager naively cope with a profession that’s quick, easy cash. They create a process, a standard of procedure so to speak, that tries to make the work that much less degrading but with each client, a little piece of their humanity is chipped away. Simultaneously, a methodical serial killer abducts the women he previously surveillances from off the street, chains them to a bed in a remote room, takes snapshots of them in confinement, and slowly starves them to death, which could last months. The two stories are intertwined and connected by a gender dominance disease in which a slow resistance begins to build to an explosive head.

The unofficial sobriquet of the Queen of Feminism Marleen Gorris had made a name for herself as a staunch supporter of feminism and lesbianism with her controversial and provocative films. Her acclaimed 1982 debut written-and-directed “A Question of Silence” show oppressed gender solidarity and mutiny against a systematically enslaved masculine society. Continuing her crusade against the patriarchal grain, Gorris followed up “A Question of Silence” with another powerfully messaged, social commentary film that, again, places women emotions and safety under the unyielding thumb of men two years later with “Broken Mirrors.” Natively known in the Netherlands as “Gebroken Spiegels,” the film marks the return of select cast from her inaugural feature, marshalling in a new narrative in the neo-feminism cinema under the returning production company Sigma Film Productions with producer Matthijs van Heijningen (“A Woman Like Eve,” “The Cool Lakes of Death.”).

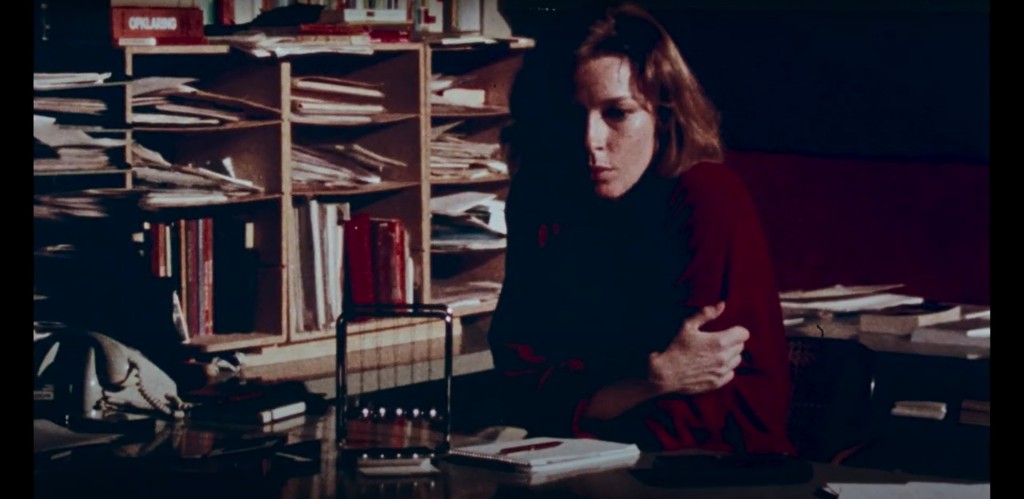

As mentioned, a pair of actresses have carried over from “A Question of Silence” to maintain a principal performance in “Broken Mirrors,” beginning with Henriëtte Tol who played the outwitting secretary in Gorri’s debut returns as a woman working in Amsterdam’s red-light district as a seasoned employee of the Happy House Club. Tol ups the ferocity levels of her previous performance while still maintaining a gradually steady sex appeal. Another returning actress who nearly didn’t have any dialogue in her previous role as a mother without a voice is Edda Barends now in a character that can’t stop screaming for her life as the latest abductee chained to a cruddy bed in a cruddy room with a coming-and-going, polaroid-enthused sociopath. In Barends starkly different rage against the man machine archetype, the actress finds herself discomposed in the face man she can’t understand but eventually recognizes his nasty need and withdraws it. Both women excel beyond the unsavory current conditions and transfer the power that’s been dangling over their heads into themselves. Newcomer Diane, played by Lineke Rijxman, becomes the key to initiate the unraveling of power of a man-owned brothel that subjugates women not as mere employees of a man-owned business but as nothing more than moneymaking ass-shakers and back-layers. Rijxman puts in the work of having her character be resilient at work and at home as she juggles a wide variety of disgusting clients to please their whims while coming home to deal with a junkie husband’s mess. As the story progresses and the women fall deeper under life’s heel, Dora and Diane spark what begins as a mutual friendship that slips gradually into sexual tension, giving them more assurances when they need it the most as the brothel parties become bigger and more intense. The parallel story runs along the same oppressive path but in unconventional, unlawful, and inhuman way with the kidnap and starvation torture of a young mother. Eddie Brugman is also a returning “A Question of Silence” actor who now finds himself in the shoes of Jean-Pierre, a mild-manner husband and by all rights societally normal seemingly man who visits the brothel for a quickie, easy money as Francine (Marijke Veugelers) would proclaim, but his dark hobby is to snatch unsuspecting women for his own perverse pleasure of watching and hearing them plea for their lives. By the end of both stories, connected by Jean-Pierre and who finds himself at the end of the disappointing stick for his kicks, crafts more than one way to not give in and to stand up against male malarkey and nastiness. The cast rounds out with Carla Hardy, Coby Stunnenberg, Anke van ‘t Hof, Elja Pelgrom, Hedda Oledzky, Arline Renfurm, Johan Leysen, Wim Wama, and Elsje de Wiljn.

Not only is “Broken Mirrors” another contentious and provocative incendiary story that wedges apart men and women, with the latter being victimized and justified in their actions, but Marleen Gorris also directs one hell of a boiling point intertwining between parallelisms that almost have no link to each other until the reveal. Gorris doesn’t necessarily employ red herrings to keep audiences guessing but rather keep the killer obscure, as all that we are exposed to see is from behind the man, who doesn’t speak much either and if he does speak, his responses are to the point with as little descriptors and adjectives as possible. Not only is the editing between simultaneous stories organic but also the other editing techniques that materialize the characters’ emotional decaying befit the mostly linear structure, such as with the student party montage at the brothel that does a roundtable of individualized scenarios between the women and their slimeball clients in an emotionally painful grin-and-bear it series that culminates to which one character best describes the ordeal as feeling like a human lavatory. The feeling is very much mutual with viewers as well, like a used wet nap to scrub off a soul staining filth covering head to toe, as Gorris represents a thematic exactitude of fiercely dividing feminism that would define her career. A clear understanding of how brothels operate is greatly depicted with that flimsy layer of excitement and efficiency to mask the ugliness underneath.

“Broken Mirrors” arrives on a Blu-ray home video from Cult Epics and, once again, resurrects and restores a pièce de résistance of Netherland celluloid. The new 4K high-definition transfer from the original 35mm negative is presented in European widescreen 1.66:1 aspect ratio on an AVC encoded, 1080p, BD50. 35mm print looks none worse the wear over the course of father time with a mint print. Restored color graded has freshened up the natural print palette of the brothel story while the kidnapper’s tale sustains a grayscale to bisect the narrative and the delineation for both presents a palatable depth. The aplenty natural grain doesn’t swarm and takeover the higher pixelations to award us with a satisfying vintage image that now enriched without any smoothing enhancements nor any compression issues to note. The Danish language release comes with two audio tracks: A DTS-HD MA 2.0 Mono and a LPCM 2.0 Mono. “Broken Mirrors” fair well from both dual channel formats with the DTS-HD aggrandizing the Lodewijk de Boer razor synth score with intent that in itself is a character. Comparatively elsewhere, the two outputs offer little differences and sate with forefront dialogue, balanced in front an equally balanced ambient track. Optional error-free English subtitles are available with haste text to keep up with the fast-paced Dutch. Special features include an audio commentary by Leiden University film scholar Peter Verstraten, an archived 1984 interview with U.S. sex worker and activist Margo St. James with Cinema 3 host Adriaan van Dis, a promotional still gallery, and trailers. The Cult Epics Blu-ray comes in a clear, traditional snapper sporting the film’s most iconic and titular moment, displayed also on the disc art, while the reverse side of the cover depicts a still image of Carla Hardy. The region free Blu runs at a not rated 110 minutes. A good double bill against “A Question of Silence,” “Broken Mirrors” makes for a morosely on the trot sister feature in more ways than one to further a Marleen Gorris artfully aired agenda.

The Best Depiction of the Unpleasant Side of Brothels. “Broken Mirrors” on Blu-ray.